by Thomas V. Banfield, CDR, USNR (Ret.), November 2000

To return to memories of the SS 320,

click here.

To return to the main page of the SS 320, click here.

Memories of Thomas V. Banfield, '57 - '58

Romance

Underway, 1957-1958

by Thomas V. Banfield, CDR, USNR (Ret.), November 2000

The Romance Begins On 22 July 1957, as a LTJG fresh out of Submarine School, I boarded Bergall at the U.S. Submarine Base in Groton, Connecticut. When you graduate from Sub School, you get to pick your sub according to your class standing. My decision was driven by romance. I was engaged to a French girl that I met the previous summer on a destroyer Med cruise, so, I wanted a boat that would be going to Europe. When my time came to pick, I saw that Bergall was available and that it was scheduled to go to England and then to the Med that fall. After checking around and finding that the boat had a good reputation, it didn’t take me long to decide. It turned out to be a great choice. So, as I pursued my personal romance, a romance with a submarine began. Bergall, along with its officers and crew, played an important and memorable role in my life and marriage.

One of our stops in the Med was to be Monte Carlo. That was perfect for me. By exchange of oceanic snail mail, my fiancée and I made plans to meet in Weymouth, England, just a short hop from Paris, and then again in the Med in Monte Carlo. Her parents were to come with her to Monte Carlo so we could celebrate our engagement there. Before leaving CONUS, I ordered an engagement ring that was to be shipped to Bergall’s FPO address.

We operated in and around New London for the rest of the summer and then on 31 August 1957 we headed across the Atlantic for England and the Mediterranean.

The officers that I remember being on board at that time were:

LCDR Elmer H. Kiehl, Captain

LT Charles F. "Chick" Rauch, Executive Officer

LT Henry. D. "Hank" Hukill

LTJG Thomas V. Banfield

LTJG John Q. Hargrove

To Scotland and England Crossing the Atlantic consisted of the usual submarine operations and training. I remember standing bridge watches off of the coast of France in heavy seas, riding up and down huge waves. We then proceeded up the west coast of England through the Sea of Ireland, and pulled into Rothesay, Scotland, our first port of call. Rothesay is located in Northern Scotland in the Firth of Clyde that provides access to the Port of Glasgow. We arrived there on Friday, 13 September and stayed two days. I didn’t go ashore because I traded duty days so I could have time off when we got to Weymouth.

Two weeks later we docked in Portland Harbor, Weymouth, England where we stayed for two days (1 - 2 October 1957). I was happy to find my fiancée there, according to plans. We enjoyed visiting Weymouth, but I started to worry about the engagement ring. I would look for it every mail call but it never showed up. Just before we got underway I crossed over to the US tender we were moored alongside and asked the ship’s post office about my ring -- but they were of no help. What was I going to do if I didn’t have the ring by the time we got to Monte Carlo? Then I noticed a pile of empty mailbags on deck and it dawned on me that a small package with a ring might have somehow gotten stuck in a mailbag. I went through all of them looking for my ring and feeling rather foolish about it. Lo and behold, as I turned the last bag upside down, a small package dropped out on the deck.

That was typical of my experiences on Bergall. Good things happened. It was a fine boat with a superb Captain and Exec. We had interesting operations, the crew was great, and we had fun.

Here is a photo of me with the bridge watch, somewhere in the Med in October 1957.

|

|

On 18 October we anchored in Piraeus Harbor, Piraeus being the seaport for nearby landlocked Athens. I remember only two things about that stay in Athens. First, upon arrival I received a letter from my fiancée telling me that she could not meet me there and, after a few anxious telephone calls, we agreed to try to meet in Rome a few weeks later if I could get leave. Now, to take leave in the Med you had to get permission from ComSixFleet. So the Captain sent a message requesting leave for me for one week, but according to the rules, leave messages had to be sent “deferred” priority. I figured, even with deferred priority, there should be plenty of time for my leave to be granted by the time we reached Malta.

The second event I remember, is that, while swinging around the hook one evening in Piraeus harbor, we got an emergency sortie alert. Several unidentified aircraft were detected heading across the Med during the night and we were ordered to be ready to get underway at short notice. Captain Elmer Kiehl was ashore, but in true submarine fashion we got ready to get underway without him. The diesels were lighted off, we set the “special sea and anchor detail", the anchor was hauled in to short stay and the diving officer was calculating the trim. Being the duty officer that night, I was standing on the bridge with the Exec (LT Charles “Chick” Rauch) waiting for further orders when we spotted a light in the harbor heading toward us. It turned out to be a motor whaleboat bringing the Captain back to Bergall. When he boarded, he came right up to the bridge, seemed impressed that all preparations were made and asked how long it took us. The Exec told him it took only about 30 minutes after we received the alert. Then he added, “It would have been a lot faster, but it took me a while to move all my gear into your stateroom.”

Shortly after that, the alert was canceled and, with a feeling of disappointment, we shut down for the night.

|

Corinth Canal. Greece 1957 |

My memory is a bit foggy about our other ports-of-call in the Med but I remember going through the Corinth Canal in southern Greece. The canal links the Gulf of Corinth on the east with the Gulf of Patras on the west, thus aiding small ship traffic between the Aegean and Ionian seas. Julius Caesar ordered the first attempt to build the canal and there were several more over the centuries, but it was not completed until 1893.

Most of us were unaware of the role played in history by this part of the world. Southern Greece is connected to the rest of Greece by a stretch of land only about six miles wide, called the Corinthian Isthmus. It has been a strategic spot during many wars fought over hundreds of centuries of Greek history. The most important was probably the war waged by Theban General Epaminondas against the invincible Spartans in the year 369. In the middle of winter that year, Epaminondas led his army of 20,000 across the Corinthian Isthmus on his way to defeat the Spartans in the name of democracy and freedom from slavery. This march of Epaminondas has been likened with General Patton’s march across France and Germany in World War II, nearly 16 centuries later.

Getting back to operations in the Med, we took part in a big NATO war game where we were trying to track down an “enemy” carrier that, along with its battle group, trying to find us before we found them. I had the 2000-2400 watch on the surface headed toward where we thought the carrier was. My orders were to dive on any sign of aircraft. Since we are the silent service, we used no radar. The lookouts and I were scanning the skies with binoculars glued to our eyes. The quiet night was disturbed when a lookout reported “aircraft at 020”! Swinging around to that bearing I saw, low on the horizon, exactly what you would expect to see with an approaching airplane, including flashing red and green running lights. I waited just long enough to determine that the bearing was steady and then I ordered, “dive” -- “dive", and down we went --to avoid the pesky oncoming aircraft. After a while, seeing nothing through the periscope, we surfaced and observed that the offending light was still there, low on the horizon. After careful study, the Navigator informed us, “Banfield’s aircraft is exactly where the planet Mars should be." I had dived from the planet Mars! Now hear this: if you go out to look at the evening sky and look closely enough at Mars, you will see a faint red glow -- and then if you look at it even more carefully, you will see red and green blinking running lights. Really you will.

|

|

Malta After playing war games for several days, we pulled into the port of Valletta, Malta. Malta is an island of strategic importance because of its location. Being right in the middle of the Mediterranean between Sicily and Africa, Malta is in position to control ship traffic across the Med as well as aircraft traffic between Europe and Africa. It has been occupied successively by civilizations seeking power, including the Phoenicians, Greeks, Carthaginians, Romans, Saracens, and Normans. It became French in 1798 under Napoleon and British in 1800. Under British control, Malta played an important role for the Allies in World War II and courageously survived intensive German bombardment. The country became independent in 1964.

Despite this intriguing history, I was more interested in getting off to Rome to meet my fiancée. I checked on what flights were available from Malta to Rome and waited anxiously for COMSIXFLT to approve my leave. No luck however. It was time to leave Malta. As we headed out to sea, the Skipper told me that if my leave message came in by 1000 he would take me back to Malta because the navigator figured they would still get to our assigned operations on time by going full speed on the surface. That is the kind of Captain Elmer Kiehl was -- a real pleasure to serve under. The message approving my leave, however, didn’t come until the next day.

Our next port-of-call was the Greek port of Patras (or Patrai on some maps) where we docked on 8 November. As soon as I could leave Bergall, I got on a narrow-gage railroad and enjoyed a picturesque ride along the coast toward Athens. From there, I took a plane to Rome to join my fiancée and future in-laws. We had our engagement dinner at a charming old restaurant and spent some time enjoying Rome. On 16 November I took a train to Naples where I re-boarded Bergall.

We did some exercises near Naples and went back there on 22 November, and then headed to Gibraltar for the mandatory refueling stop on 26 November. We got underway at midnight to transit the Atlantic, due to return to New London on 7 December. We encountered rough seas, however, for most of the way back, so we did not pull in to New London until 1400 on 8 December.

Lt. Charles F. Rauch

Bergall Executive Officer

On 21 December 1957, I was married in a military ceremony in my hometown in Pennsylvania. I was honored to have both the Captain and the Exec of Bergall serve as ushers. Here are their photos taken at the wedding.

LCDR Elmer H. Kiehl

Bergall Captain

Here's my lovely bride, Jacqueline, and

myself on that wonderful day!

Here's my lovely bride, Jacqueline, and

myself on that wonderful day!

Bergall got underway again on 1 February 1958 for operations and

a stop in Bermuda. I think we were there for only a day or two but

Bermuda is a great stop, especially in February when you can enjoy the good

weather and the pink sands of Bermuda.

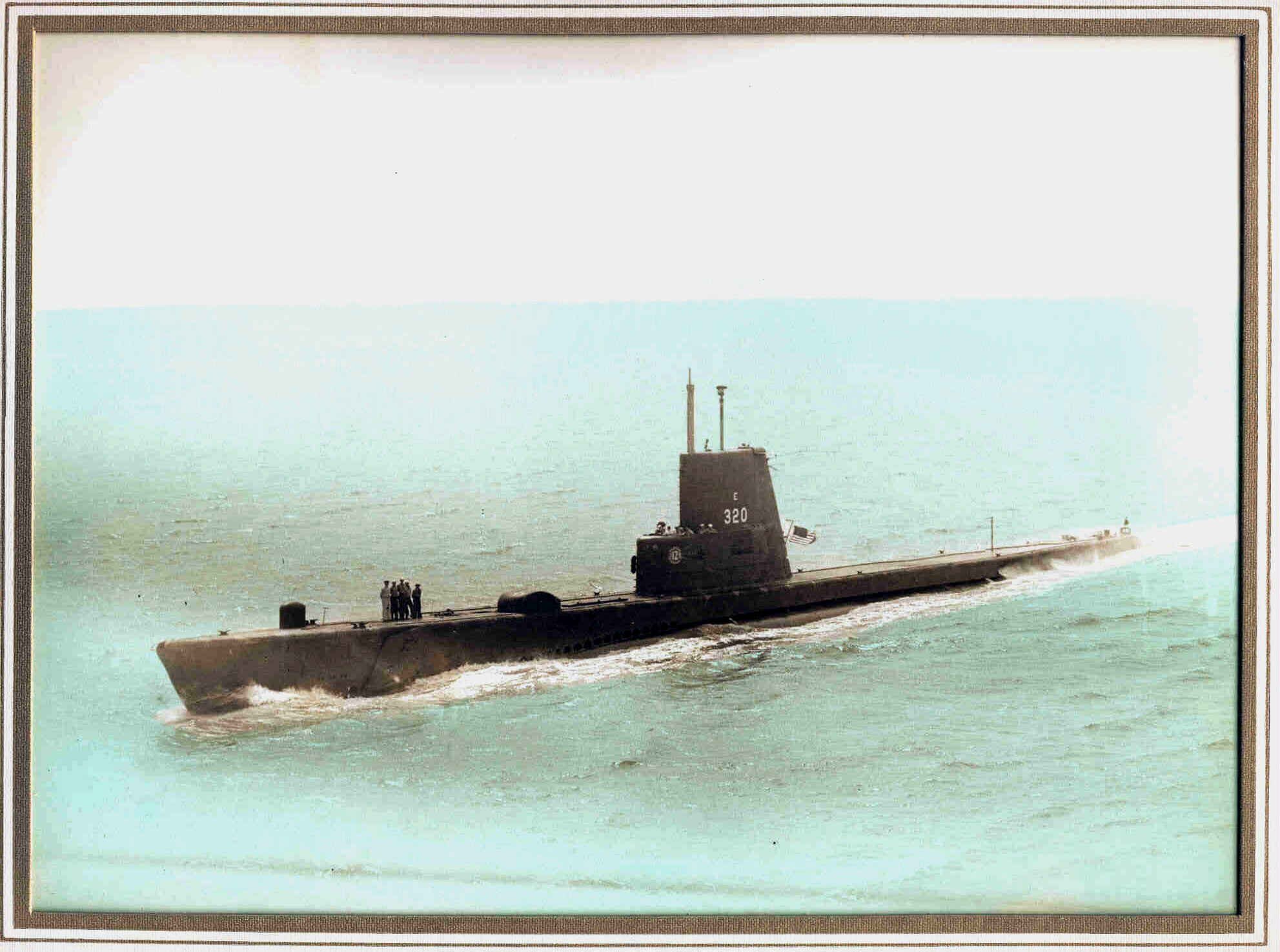

Here's a shot of her, probably taken in 1958 before the transfer to Key West (Because of the Efficiency "E" and the Squadron 12 emblem.).

Then we went back to New

London and were underway again on 26 February 1958 to participate in the annual

“Operation Springboard”.

Operation Springboard 1958 To Navy wives Operation Springboard is when the husbands leave snow shovels to their wives and head for the sunny, warm waters of Caribbean. We played target sub in various ASW operations out of San Juan and St. Thomas. While there, we enjoyed an unusual operational assignment that amounted to daily operations out of St. Thomas. A contingent of the U.S. Marine Underwater Demolition Team (UDT) came on board each day and we would go out to an inlet on the island where we would submerge and sit on the bottom. We locked the UDT guys out of the forward escape trunk and they would find their way to the beach and spend the day playing “jungle bunny”. Then they would see if they could get back to the sub when we surfaced to pick them up.

It was hot and boring sitting on the bottom. There was no air conditioning because we had to stop all cooling water circulation -- lest we suck sand into the system. So, on some of those days, we sent one third of the crew ashore with some beer and hot dogs. After submerging we would lock out another third of the crew through the escape hatch for escape training. After a long hard day we would return to Charlotte Amalie to enjoy some rum and calypso music.

After I did my practice escape, I was floating around in my life jacket waiting for Bergall to surface. I could duck my head under water and easily see the boat in the clear waters of the Caribbean. Soon I realized that Bergall was coming up. I thought it would be a clever trick to surprise whoever was going to open the hatch after surfacing, if I would already be on the bridge! I maneuvered myself into position so that I was just above the bridge as she made her assent. It was a piece of cake. The sail came up behind me and the next thing I knew I was on the bridge hanging on while tons of water flowed off of it. Then the conning tower hatch was cracked open and up came Captain Kiehl, whom I greeted with glee. Could that be the first time in history that a sub surfaced and found a live body topside?

Transfer to Key West When we returned to New London on 28 March we found out that, effective 14 July, Bergall and Spikefish (SS 404) were ordered to change home ports from New London to Key West. In early May we were underway for two weeks of operations and a short visit in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Then we were busy getting ready for our transfer to Key West, which included some changes in crew and officer assignments.

I became Engineer Officer on 23 June but I was among those who were allowed to drive to Key West rather than making the transit on board. Maybe it was mostly the bachelors who made the transit.

Upon arrival in Key West we sublet a house from someone who was in the Charleston shipyard for overhaul and I bought a used Vespa motor scooter for $125 to get to and from the piers. Soon after, we signed a contract to build a house, which got built but we were never to live in it. That is because Bergall received orders to transfer to the Turkish Navy.

My romance with a submarine was about to end, but the other romance continues. My wife and I will be celebrating our 43rd Anniversary this December – with fond memories of a great boat.

The Bergall Transition to The Turkish Navy in 1958

I note that elsewhere on this site it says the Bergall was transferred from New London to Key West in preparation for the transfer to Turkey. That doesn't seem right, because why would the Navy would have gone to all the expense, moving all the families, etc., just for an outfitting stay of a few months. Further, there was nothing we did in the preparations for the transfer to Turkey that couldn't have been done just as easily in New London. In any case, we did not know about the transfer until we got down there. It came as quite a surprise to us. Some of us even bought houses -- me included.

Here is the whole story.

On the Bergall, I was a Lt. and the Engineering Officer.

Soon after the change of home ports from New London to Key West on 14 July 1958,

Bergall was ordered to be transferred to the Turkish Navy under the Military

Assistance Program (MAP). Bergall was chosen because she was

converted from the WW II "fleet boat" design to a snorkel sub, a design that

became known as a "fleet snorkel", but she did not have the more advanced

"guppy" conversion that would have given her a sleeker bow with faster submerged

speeds. The Turks needed a snorkel sub but the Navy did not need to

give away a boat with the full guppy conversion.

The military significance of this transfer is interesting. The Turks control the ship traffic in and out of the Black Sea through the Bosporus Straits as well as through the Straits of Dardanelles. The Turks own the land on both sides of these strategic waterways and the control of ship traffic is carried out in strict accordance with the Montreux Convention of 1936. Under this Convention, the Turks allowed relatively free passage of ships belonging to the Black Sea powers, which included Russia, but much stricter controls were placed on submarines. In case of war, or even if the Turks felt threatened by war, they could act under their own discretion.

The Russians had about 200 subs (about half of their submarine fleet) in the Black Sea. There in the moderate climate, they could conduct year-round, ice-free operations, but they could not rely on being able to get any of their subs out of the Black Sea if they needed them elsewhere. Consequently, Russian submarine operations in the Black sea were principally for training.

In the international scheme of things, what was the role of the Turkish submarine force? From both economic and military standpoints, the Russians were highly dependent on ship traffic across the Black Sea. There was only one railway that effectively served the commercial and military traffic in this part of the Soviet Union. Thus, it was important for the Allies to have the ability to attack this ship traffic in the event of war. However, the Russians could easily mine the entrance to the Bosporus Strait, preventing any traffic from getting into or out of the Black sea. It was therefore left to the Turks to be sure they always had some subs in the Black Sea in case the balloon went up, knowing that there were only slim chances of ever returning home. Subs without a snorkel capability would have to surface to charge batteries and would not last long against the Soviet radar and ASW capability. Even with snorkel capability, I became relieved to know that the Turks would have this duty, not one of our US subs.

We were scheduled to depart 26 September 1958 so we had lots of work to do to prepare for the transfer. New batteries were installed and we put Turkish name tags on all the valves and switches. During the preparation, things like flashlights and screw drivers started to disappear? I remember our Skipper, Elmer Kiehl, thinking that one solution would be to buy enough flashlights and screw drivers so that everyone on board would have one for each closet at home plus the glove compartment in the car. As things started disappearing, I got the chiefs together and told them to pass the word that we would be sailing Bergall across the Atlantic and would be doing some submerged operations before turning it over to the Turks and to be sure that we had a full inventory of tools and parts. They assured me that we would, and we did.

Bergall transited the Atlantic on the surface in almost glassy calm seas, somewhat unexpected because it was hurricane season. We did the routine refueling in Gibraltar on 9 October and then sailed on to Izmir Turkey, arriving there 15 October, where Bergall was to be decommissioned and recommissioned as the as the TCG Turgutreis (S-342).

That ceremony took place topside, moored along side the pier in Izmir on 17 October 1958. Based on a combination of what I could find in my files and my memory, the roster of officers of the decommissioning crew was as follows:

LCDR Elmer H. Kiehl, Captain

LCDR Leonard J. Kojm, Executive Officer

LT Charles G. Tate, Operations Officer & Navigator

LT Thomas V. Banfield, Engineer Officer

LT John Q. Hargrove

LT Joseph Anderson

LTJG John G. Thomas

ENS Ralph R. Maddox

We didn't think much about the ceremony as we casually made preparations. Most of us had gone through change of command ceremonies before. When it came time, however, to come to attention and watch the stars and stripes being lowered down the stern mast for the last time, emotions began to creep into the cold , mater-of-fact, military composures. And that's when we realized that we were not just standing on another mass of steel and machinery. It was the USS Bergall. She had a history and a personality. To many of us, she was more of a home than a place of employment. She had been part of our lives. The telltale signs of the emotions were the deep breaths and quite a few Adam's apples bobbing up and down among the officers and men.

Major General A. D. MEAD said, at the change of command, "To the brave personnel of USS Bergall, you will soon turn over this ship which you have honorably manned under the American flag, to serve under the Turkish flag, to your colleagues whose friendship and generosity you have tried and learned both in peace and in battlefield. I well appreciate the affection you cherish for your beautiful ship to whom you are died with such unforgettable memories at sea. I sympathize with you for the human and personal sorrow you will experience when parting with it. but I must assure you of the fact that your Turkish colleagues to whom you will entrust your beloved ship will love her with as strong and affection as yours and will use her for the realization of our common ideals. For this reason, you may go to your new duties with a relaxed conscience. I wish you good luck in your professional life and happiness for the years to come."

Then, with the raising of the Turkish flag it was all over. Most of the crew went back to the States. Some of us, the Captain (Elmer Kiehl), the Exec (Leonard Kojm) and yours truly as Engineer Officer, along with several chiefs stayed in Turkey as part of a Mobile Training Unit. Most of the Turkish crew had been through Sub School at New London, had served on other US built subs in their Navy and were qualified submariners. So our job was to train them in snorkeling and on any other equipment or procedures that were new to them. But the Turkish sub base and operating areas were not at Izmir in southern Turkey, they were located north of the Dardanelles at Golcuk on the Sea of Marmora.

Why didn't the change of command take place at Golcuk? The answer has to do with the Montreux Convention, discussed previously. Only submarines belonging to the Balkan States are permitted to transit the Dardanelles, and then only during the day and with advance notice. Since the United States was not a Balkan state, Bergall could not make the transit under the US flag. The change of command had to take place before going to the sub base at Golcuk. What's more, even under their own flag, the Turks would not allow any of the US training crew on board during the transit. So, after getting the Turkish Captain to promise not to submerge during the transit, we flew to Golcuk, and waited for Turgutreis to arrive. This was accomplished without any apparent difficulty and, soon after, we commenced training at Golcuk.

One of the differences in the Turkish Navy is that everything on board ship becomes the personal responsibility of someone in the crew. An inventory was carried out and every item was signed for by a petty officer, a chief or an officer, whether it was a wrench, a pair of binoculars or a diesel engine. It seems that if something is lost, the signer could be docked in pay up to some limit, which I think might have been 10% of pay until the item is paid for. We think this became a factor when it came time to do a torpedo shoot. As in our Navy, a practice torpedo shoot consists of firing a torpedo fitted with an "exercise head" instead of a warhead. At the end of the torpedo run the exercise head releases a flotation device that keeps the torpedo afloat so it can be recovered. Each day we were to do the shoot, the Captain would postpone it, saying the sea was too rough for recovery. This seemed to us to be overly cautious because the sea, although choppy, was not too rough to recover a torpedo. Then we realized that if the torpedo was lost the Captain might have to pay for it. In 1958, Turkish Commanders received the equivalent of $90 per month, including submarine pay. It would take a long time to pay for a torpedo. Sure enough, a day came when the Sea of Marmora was flat calm and we did the shoot. The torpedo was found and recovered without difficulty.

Soon after that, the Turkish Captain was at the Conn making a practice torpedo attack on a target destroyer escort. Taking frequent periscope sightings, he patiently stalked the zigzagging target until he closed the distance to a very close 1500 yards and raised the scope for a final look. He saw that the target had turned to give him an easy shot, broad on the beam. He ordered "shoot" and we gave him credit for a skillful "kill.". Then, Elmer Kiehl, asked him what he would have done, if at the final periscope observation, the target had turned toward the sub instead of away. In that situation, a surface ship coming at close range with a zero angle on the bow, the proper action would be to order full dive on both planes, flood negative tank and get down to at least 100 feet as fast as possible. At that depth the keel of the surface ship could pass safely overhead. The response we got from the Turkish Skipper was that he would surface! Surprised by this answer, Kiehl asked why? The response was the Turkish Skipper said, "I'll show you why." and ordered "Full dive both planes, flood negative, 15 degree down bubble, make your depth 100 feet.". Turgutreis nosed over and started down. But the descent soon stopped leaving the sub hanging at a dangerous depth, a depth too deep to use the periscope and too shallow to keep from being struck by a surface ship. What happened? Well, we learned that the Sea of Marmora is a mixture of salt water from the Mediterranean and fresh water from the Black Sea. This mixture stratifies with the fresh water on top and the more dense salt water on the bottom. Getting down to 100 feet would have taken about 10 more minutes of flooding water into the trim tanks.

It was not until then that I understood why the Turks were always taking sea samples and measuring the specific gravity. As Engineer with a brand new battery, I was constantly trying to find out the specific gravity of the battery electrolyte, to determine the state of battery charge and the Turks were more concerned about the specific gravity of the sea water! It turned out that in the Sea of Marmora this was critical information to be able to calculate the diving trim. A sub with the trim adjusted for salt water would sink like a rock in fresh water. And we were worried about the Turks submerging without us on board!

Throughout this period with the Turks we learned to respect them for their friendship, their sincerity, and their professional competency. We were invited into their homes and gained an appreciation for folks who live with much more modest means than we are used to. From a military standpoint, we were glad that we had them as an Ally.

On November 16, after the 4-week training period, we said good-by to our Turkish friends knowing that we were leaving Bergall, now Turgutreis in good hands. We left Golcuk, headed to Istanbul to board a Pam Am flight over the Austrian Alps to Paris and then to New York and Key West.

Thomas Banfield

To return to memories of the SS 320,

click here.

To return to the main page of the SS 320, click here.