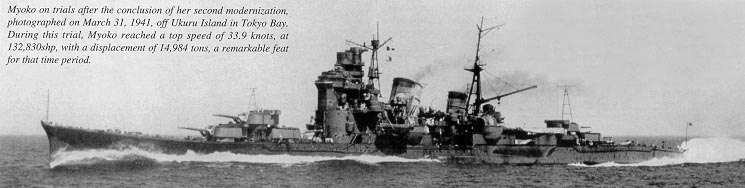

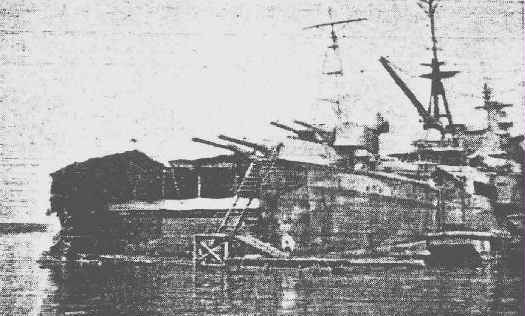

This is approximately the angle that the Bergall had on the Myoko.

by Anthony Tully, December 1999 residan@connect.net

Note: All times set to Z-9, Item time.

The Pacific War is full of epic stories both of combat between vessels, and the even older battle of men & ships against the perils of the sea. One of the lesser known encounters and epic damage control fights came fifty-five years ago in December 1944, when U.S.S. BERGALL engaged IJN MYOKO. A fascinating twist of fate would bring these two together, and see them both fighting to stay afloat against the odds.

The encounter had its beginnings at 1630 on 5 December, 1944, when USS BERGALL (SS-320) under command of Commander J.M. Hyde departed Exmouth Gulf, Australia bound for her assigned war patrol off the Malayan and Indo-China coasts. Tagging along with Hyde on Commander's training this journey was PCO Ben Jarvis, whose previous service included USS Nautilus and Sailfish. It would prove to be an curriculum. On this journey BERGALL (and the Dace on the same general mission) carried a load of anchored mines in her aft torpedo tubes. The plan was to lay these off the Indochina coast, along the long reef called Royalist Bank. BERGALL’s course was plotted to take her around the eastern end of Java, via Lombok Strait, then westward through the Flores Sea and finally through Karimata Strait. This was the plan, and was followed.

As it so happened, at 1205 that same 5 December, the IJN heavy cruiser MYOKO at Singapore received orders from Combined Fleet. The MYOKO had been under repair ever since being damaged on 23 October, 1944 en route with the First Striking Force headed for the Battle of Leyte Gulf. An aerial torpedo had struck on the starboard side under the mainmast, flooding the after engine room and generator room. Too crippled to participate further, the MYOKO had limped back to Brunei, and ultimately to Singapore, arriving on 2 November. She had been under repair since at Seletar Naval Dockyard. Now Tokyo judged those repairs sufficiently advanced for the MYOKO to attempt the journey home for full repairs. According to the orders, Captain Hajime Ishiwara of the MYOKO was instructed to depart with USHIO for the Inland Sea in company with a homeland-bound convoy "on or about 9 December. " Preparations were accordingly made.

However, come 9 December, the MYOKO’s departure was delayed. The postponement proved fateful indeed. For on the morning of 9 December, BERGALL was just emerging from Lombok Strait. Had MYOKO sailed on schedule, the two ships would never have met. Instead, the stage was set for an eventful encounter and mutual drama of survival.

Commander Hyde of BERGALL of course was not aware of this, and was expecting nothing particularly unusual about this patrol save for the optimistic hopes always entertained but seldom realized. His fairly new boat was only on its second patrol, and made good progress across the Flores Sea. However, a major fly in the ointment appeared on 11 December. During routine inspection of the torpedoes, it was found that #5 and #6 both had developed leaks, and had lost considerable air pressure. Though #6 was pulled out for examination, #5 remained in the tube.

The next day, at 0700 12 December, the cruiser MYOKO and destroyer USHIO got underway from Singapore, heading for Japan via Camranh Bay. In a sense, it was the blind leading the blind so to speak, in that both vessels were damaged. For the USHIO had been damaged also in an air attack at Manila on 13 November, and had lost the use of her starboard turbine. This limited her to 18 knots, but since MYOKO could barely make 16, this made no difference. They were the perfect pair to go home together, and for the voyage the USHIO was placed under command of MYOKO's captain.

So it came to pass that sunset of 13 December found the MYOKO and the BERGALL converging off Royalist Bank. The day had not passed without incident. There was great activity in the airwaves, for the Japanese had sighted an enemy invasion convoy passing west through the Sulu Sea. It was in fact, the Mindoro invasion force, but the Japanese did not yet know this. For all they knew, it was the long-feared invasion of Luzon. A flurry of activity followed as Southwest Area Fleet and Tokyo scrambled to prepare for the invasion whereever it might land.

The Second Striking Force of VADm Kiyohide Shima had departed Lingga for St. James the same hour MYOKO and USHIO left Singapore, and thus was already en route to a good standby position. Shima was ordered to wait at St. James and prepare for a surface counter-attack the moment the enemy's intentions were discovered. Meanwhile, MYOKO and USHIO probably heard the flurry of messages and orders passing across the airwaves, but as it happened, none were directed to them. Their original orders apparently stood; to proceed to the western Inland Sea for docking and repairs. There remained, of course, a slight chance that the partly-operational heavy cruiser might yet be "drafted" for sudden duty after arriving at Saigon.

It was now there appeared a factor that was to foil original orders, and erase any possibility of involvement in new ones. It would be the catalyst that set off one of the largest and least-known salvage operations in Imperial Navy history. This would play a heretofore unrecognized role in distracting and disrupting Japanese Navy countermoves against Mindoro till the beachhead was well established. This factor and catalyst was the none other than USS BERGALL now arrived and preparing to lay her mines off Royalist Bank.

This was an extensive reef, and BERGALL had been assigned to mine a section corresponding to a locale termed `Point Decamo'. Sunset was approaching, and the mining would take place that night. Hyde's boat was just edging in over shallow water and PCO Jarvis was in the wardroom when suddenly a high-powered radio signal that blanked their receiver was reported. That meant a powerful transmitter, and Jarvis informed the skipper. He then immediately manned the #2 periscope used for long-range spotting, and began scanning in all directions. His vigilance was rewarded: at 1755 a ship was sighted bearing 105, nearly due east, range 35,000 yards heading on a NE course at about 14 knots. The mast appeared "stick-like", a high, non-commercial radar aerial. From his previous experience CPO Jarvis was convinced it was a man-of-war type mast, and Hyde agreed. The skipper immediately swung the boat around and put all four engines on maximum speed to try to get ahead of the ship's track. By 1845 BERGALL was gaining only very slowly, but the vibration of the engines was so great Hyde was reluctantly forced to slow to 18 knots. Thirty-five minutes later he was rewarded when radar reported a firm contact at 26,000 yards, bearing steady at 102 degrees. BERGALL had made position.

By 2011 the target was clearly in sight, on course 055 making about 16 knots, and was seen to have been worth the chase. She was a large warship with a single escort ahead of her starboard bow, that is, the opposite side from where BERGALL was closing in. It remained for the submarine to attack. Twenty minutes later Hyde and his officers caught their breath. The target was seen to be a heavy cruiser of the ATAGO or TONE class, and the escort a light cruiser. Though a thrilling target, it was also incredibly dangerous: such a vessel could easily blow the BERGALL out of the water. Nor could a submerged approach be tried, the waters were too shallow. Finally, with her aft tubes filled with mines, any attack angle would have to be made with the bow tubes only.

Undaunted by all these obstacles, Hyde decided to run BERGALL in under cover of the rapidly darkening skies like a PT boat. He had to hope that the cruiser's radar, detected making slow sweeps with long intervals of silence, did not pick him up too soon. There was one advantage; the escort was on the far side. At 2135 Hyde saw the escort drop back to a position abeam of the target and blinker a signal. This was the moment, when both ships were overlapped, the escort's bridge and bow extending beyond the cruiser's! Two minutes later, BERGALL commenced firing all bow tubes (including leaking #5 torpedo) at a range of 3,300 yards, depth set for six feet on a track spread ranging from 112 to 121 degrees port.

At 2140, at eight-second intervals, the

first and second torpedoes connected, with spectacular results.

Any further hits were completely lost in the thundering explosion

and balloon of fire that erupted. BERGALL's stunned officers

recorded in the ship's log what happened next: "2040 [2140

Item] 2 hits heard but unsure. Saw target break in two at after

end of bridge. Explosion forced two ends apart so that there were

two huge persistent fires which in ten minutes were 1,000 yards

apart. Radar now had three pips instead of two, stern section had

definite down angle toward its newly acquired "bow".

The bridge structure was completely demolished and not seen

after, although the other parts of the hull were seen. Bow

section had a decided up angle. Escort made no effort to chase

but stopped abeam of the target while we opened to 10,000

yards."

This is approximately the angle that the Bergall

had on the Myoko.

From BERGALL's log it certainly appeared that the heavy cruiser was all but finished. The damage described was catastrophic. Nor did the escort make any attempt to chase but had stopped dead--- BERGALL was inclined to believe that it had apparently been struck and damaged also. Hyde turned away to reload before returning to deliver the coup-de-grace to the escort, still assumed to be a light cruiser.

Funny just how misleading the flash and shapes of night battle can be; for though MYOKO had indeed been slammed by BERGALL's salvo, the situation was not all as it appeared, albeit grave enough. At 2140 at least one torpedo hit the cruiser on the port quarter, setting off the volatile reserve oil tanks aft. The result was the catastrophic blast Hyde had witnessed. The afterdeck was completely shattered, it seems part of the stern blown completely free. It drifted off, burning and sinking. Fires broke out around MYOKO's aft turrets, but despite appearances there was no damage to the main body of the ship forward of the mainmast.

Which is to say the MYOKO had been wounded sore, but was not at all the shattered wreck Hyde beleived he saw. The vessel was undamaged forward of the No. 5 turret though she was unable to steer. Neither had the USHIO been hit. Instead, she had drawn up alongside to determine status. While Captain Hajime Ishiwara waited for news, Commander Masaomi Araki of USHIO was setting a trap for the offending submarine. Feigning dead, he waited to lure it in. He waited until the range was 3,000 yards, then at 2200 USHIO opened fire with a well aimed two-gun salvo.

Caught by surprise, the BERGALL was nailed squarely. With truly remarkable shooting, a shell of USHIO's first salvo arced down from port, hit the back of the forward torpedo loading trunk’s hatch, tore through it, and exited out the pressure hull starboard at frame 35 without detonating. Water poured in through the resulting hole "five foot square hole in the starboard pressure hull" and the main ballast tank began venting from the damage. But no one was killed: two mess stewards whose bunks were in the overhead of the forward torpedo found their bunks filled with shrapnel and other debris. Fortunately, they had not been in them at the time!

Taken aback, Hyde lost no time ordering the helm hard over and standard speed on all four engines. It was just in time, a second pair of shells fell into the sea 200 yards off the port bow. USHIO snapped on a searchlight, sweeping, but failed to fix on the submarine. Looking down, the skipper could see that the damage was severe, with compartment fires and lights visible---the main hull was open to the air. As Hyde sped away, there came a third and last salvo, splashing water over the fleeing submarine's starboard bow. The BERGALL bent on to 18 knots, determined to put as much distance as possible between her and the enemy by daybreak, for now she could no longer dive. Daybreak was estimated at nine hours away. Mercifully, the USHIO did not pursue her, having enough concern with her charge.

Hyde and his crew had little doubt that USHIO’s charge was done for, for at 2206 he logged: "Saw a series of explosions in the bow section of the cruiser. Shortly after this the flames in the bow section appeared to die out and the radar pip disappeared on this section. A column of steam rose from it and a cloud of smoke gathered over it." It appeared certain that the target Atago-class cruiser, ablaze, broken in half, was sinking, and that the escorting light cruiser was damaged, for she had fired only one turret at BERGALL.

However, these impressions were false. It is fascinating to examine just what did happen. First off, as seen, the target’s [MYOKO’s] escort was not a cruiser, but the destroyer USHIO. BERGALL’s action report opined that she had been struck by an 8-inch shell, citing a measured 8-10-inch round hole punched through her hull. But BERGALL herself clearly observed that it was the escort that opened fire, and in any case, though her fire-control radar may have assisted USHIO, it seems unlikely that MYOKO brought her turrets to bear after being hit. Further, three two-gun salvos is perfectly consistent with the fore turret of a Fubuki-class destroyer. The vagueries of impact dynamics can be invoked to explain the discrepancy between shell and hole size. One thing seems clear: since the USHIO's main battery was 5-inch, the BERGALL must have been struck by a 5-inch shell. All of which takes nothing away from either the skill of the Japanese gunner or the BERGALLIAN's battle to save their ship the following days.

Then there is the matter of the damage observed and that actually inflicted. At request, the details have been investigated as thoroughly as possible. What happened appears to be this: At 2140, one, possibly even two of BERGALL’s torpedoes struck MYOKO in the port quarter about level with the outboard propellers. This detonated the reserve oil tanks and shattered the fantail. The MYOKO lost the use of her rudder and all but the outboard port propeller were smashed. It seems that pieces of the fantail definitely broke off, because BERGALL reported three radar pips after the explosion. After the hit, MYOKO signaled Southwest Area Fleet she could still make 6 knots on one remaining screw, but she was unable to steer. Hence, it was necessary to arrange a tow, as will be seen. Later, apparently, the damaged stern broke off further on 17 December. However, given the observations of both radar and eyewitnesses of the target being blown in two sections, and one even observed to sink, it seems something detached. Given the details of three separate pips, fires drifted 1,000 yards apart, it seems bold to dismiss them outright. Most likely, that part of the MYOKO containing the rudder was severed at impact, and oil covered, drifted away flaming to sink.

Whatever the actual hull failure damage at moment of impact, the MYOKO had been completely disabled. The fires were stubborn and continued to blaze, but the crew shored up the point of breakage, and minimal flooding had resulted. More remarkable, as noted the port outboard shaft somehow remained operable, though it projected naked from the sundered fantail. The other three props were smashed and severed. All in all, the damage was worse than that the previous October.

The MYOKO could still make 6 knots using this last shaft, so instead of evacuating his cruiser, Captain Ishiwara resolved to save her. USHIO was asked to take a tow line aboard. Captain Masomi Araki protested by signal that because of his smashed starboard engine, with the port engine alone USHIO did not have the power to tow. But the MYOKO could make 6 knots; what Ishiwara needed from USHIO was to be kept on the right heading among the waves.

The destroyer appears to have agreed, and an arduous and painful crawl began. From the 14th through the 15th the USHIOcontinued to struggle against the worsening seas, striving to keep the MYOKO from wobbling off course. Though her damaged engines could not hope to tow the full weight of the crippled cruiser, she could at least try to keep MYOKO's bow headed for St. James. The cruiser's remaining propeller did the rest, painfully shoving her forward, mile by mile.

Her attacker too, was having her troubles. After torpedoeing MYOKO, the BERGALL had retired from the scene of the action at her best surface speed. The night of the 13/14 was spent extinguishing small electrical fires started by the water coming in, and trying to move sound gear and other electrical motors away from the gash in the hull. Mattresses were stuffed into the hole to keep the spray out as best as possible. Though there was no immediate danger of further flooding, diving was still impossible. Dawn brought redoubled vigilance and manning of all available guns, for any aircraft bombing would have to be evaded on the surface. Though repairs on the hatch started at sunrise, and the holes were gradually plugged with an amalgam of mattresses, wooden pegs, and brazed plates, BERGALL could still not dive. The nearest Allied base was from whence she had came --- Exmouth Gulf, 2,000 miles away. In order to reach it, she would have to proceed on the surface in broad daylight though 1,200 miles of sky and sea patrolled by the enemy!

All in all, this made for poor prospects for survival, and though the game seemed up when a Mavis was sighted to the northwest at 1210, Commander Hyde did not give up easily. Turning away, he managed to lose the aircraft apparently without being detected. Thereupon he hit upon an idea. Instead of keeping wide of Borneo’s coast, he would run in toward it on a converging course. Hopefully, from a distance she would be taken for simply a boat headed for Brunei Bay at day’s end. The ruse appeared to work, and sunset came without incident. At 2100 Hyde felt confident enough to transmit a message of his attack, calling it appropriately enough: "Busted BERGALL’s First."

The morning of 15 December brought with it orders from TF 71.1 for BERGALL to rendevous with other boats at North Nateona. Commander Hyde was much vexed, and after careful consideration decided to disregard the order. To have complied would have required taking BERGALL back on the surface in daylight through waters she had just passed through, needlessly risking her crew. Furthermore, Hyde was betting he could make transit through Karimata Strait, across the Java Sea, and then through the Lombok Strait to Australia without encountering any aircraft. He had observed none on two previous trips along the same route, and the gamble seemed worth it. To better the odds further, he would pace his speed to pass Karimata and Lombok Straits in darkness.

The decision was made, and its wisdom soon affirmed. At 0950 15 December USS ANGLER (H. Bissel Jr. commanding) was picked up, bringing welcome company. By 1105 the two submarine skippers were alongside each other, talking by megaphone. After consultation, and hearing ANGLER’s report, Hyde was convinced he could run the gauntlet safety. Course was set for Karimata Strait, and it was decided that Angler would follow in escort. Other than the continuing leakage, the afternoon passed without a hitch, and at sunset both boats were approaching Karimata Strait. Ironically, at 1216 that day, ComSubPac had issued an order for Hyde to proceed to Dangerous Ground (reefs near Palawan Island) south of Mindoro and scuttle the BERGALL! Maintaining silence in these exposed waters, Hyde did not reply to this, nor did ANGLER. For the next few days, ComSubPac would be in the dark about the fate of BERGALL and became increasingly anxious for her safety.

For the two submarines, the next step was somewhat risky , so the decision was made at 1905 to transfer one officer and fifty-four men to the ANGLER. Commander Hyde would stick aboard with a skeleton crew to run her through the straits. With the weather so favorable - overcast with heavy rain storms from the north-northwest to foil aircraft – it seemed "unthinkable" to simply scuttle the BERGALL. Volunteers for the skeleton crew were practically unanamious, but eventually twenty-nine were chosen for the task. Planning to sit on bottom in shallows if necessary, at 2125 Hyde commenced the dash through Karimata Strait. If they were attacked, all knew the score: Hyde had ordered Bissel and ANGLER to attempt no rescue, but "save your boat and the rest of my men".

Meanwhile, far away aboard the MYOKO the fires were still raging, and were not finally doused till 15 December. As with the American boat, the 15th saw friends arriving. Two subchasers, the KAIKO and TATEBE MARUS and two minesweepers of the 21 Special Base force arrived, and the picture brightened for the Japanese cruiser. TATEBE MARU passed a true tow line, and towing commenced with MYOKO making 5 knots toward St. James. However, the same storms that were cloaking the BERGALL’s dash were making the MYOKO’s progress labored.

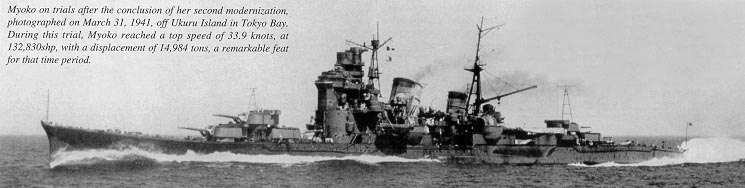

Map of BERGALL and MYOKO's encounter.

Japanese Navy Map of the general scene of the action between BERGALL and MYOKO. The BERGALL sighted MYOKO at 7-36'N, 105-12'E 13 December. According to BERGALL she attacked the cruiser at 8-10'N, 105-31'E at 2140 hours. MYOKO's signal to Combined Fleet gave the attack position as 8-8'N, 105-40'E. The chart shows the movements of Shima's 2-YB and the position of the MYOKO at 5-15'N, 104-45'E at noon 20 December.

At 0815 16 December, the limping pair were south of St. James, and Captain Ishiwara released the USHIO from her guard duty. She was unable to tow his cruiser, and needed to proceed ahead into Saigon port so as to escort convoy HI-82 due to depart the next day for Japan. The subchasers continued their work, but the seas steadily worsened and the forecast was for truly severe weather. Therefore, before noon the order came to reverse and tow MYOKO back to Singapore instead. Hopefully the waters in that direction would be more agreeable. MYOKO hove to and awaited the arrival of ships with engines in suitable shape for endurance towing. That help was soon forthcoming. At 1100 SWAF ordered DesRon 2 to prepare to send the OYODO, KASUMI, and HATSUSHIMO out to where the MYOKO lay.

At Singapore, Vice Admiral Shintaro Hashimoto heard the news of MYOKO with some distress. As she belonged to his Crudiv 5, he considered her his responsibility. Thereupon he ordered his flagship HAGURO out of dock at 1430 the 16th, boarded her, and reported that he would load supplies tomorrow and sail to MYOKO's rescue by the 18th. Since she was now in port, the CHIBURI would follow in a few days, but Hashimoto requested two additional guard ships.

MYOKO's attacker was at this time picking her way across enemy-held waters toward Java in broad daylight. The BERGALL had cleared Karimata Strait at sunrise that morning, and was plowing southeasterly with every nerve stretched to the utmost. All eyes were skyward, searching for signs of the air attack that could doom the submarine. None appeared. The 16th passed with surprising calm. The only disturbance came at the end, when at 1751 Hyde sighted the usual patrol saildboat off Bawean Island. The "sighting however" came in an unconventional way. Chuck Kennedy, wrote the author that `it was already dark, and the BERGALL was running silent. So silent that the patrol boat was detected when BERGALL's guys heard the Japanese crew on deck! Despite this rather harrowing means of detection, the patrol boat was avoided without difficulty.

The same lack of difficulty did not obtain for the Japanese efforts to assist BERGALL's victim. At 2100 16 December USHIO arrived at St.James, and sent a message emphasizing that with her storm damage and only port shaft working, that she could not tow MYOKO. A "healthy" vessel must be sent, the sooner the better. The need for haste was punctuated at 0510 the 17th when the MYOKO’s damaged stern completely parted at frame 325 due to the heavy waves. The cruiser remained afloat, but towing speed had to be cut to 2.5 knots. The situation was growing more precarious. In response to this and Admiral Hashimoto's request the KASUMI and HATSUSHIMO were ordered at 2300 the 17th to abandon their convoying of NICHEI MARU to St.James and to go to MYOKO's assistance.

That same hour, the BERGALL entered Lombok Strait on the last lap of the voyage home. ComSubPac was still in the dark about BERGALL’s safety, sending a stream of orders to fellow boats BASHAW and PADDLE that searched the seas near Mindoro in vain, fearing the worst.

By this time, bigger issues were intruding, and Mindoro was no place to be. On 15 December, the Japanese learned mysterious target of the American invasion force. They were landing near San Jose base, at Mindoro. The kamikaze attacks began even as the first soldiers waded ashore. They damaged two escort carriers and smashed two LSTs. Despite these losses, the Americans pressed home the invasion with characteristic thoroughness, and by sunset all troops had been disembarked and General Dunckel was ashore. The invasion was a success and Admiral Struble free to return to Leyte Gulf. In the following days, Onishi's kamikaze's continued to attack, but the beachhead was little effected by them. The industrious engineers went quickly to work building the planned airstrips and soon fighters were flying from Mindoro.

Southwest Area Fleet also intended that the aerial effort be supplemented by a night-surface attack on the beachhead. The only warships sufficiently close for an immediate attack, so important with landings, was the Matsu-class escort destroyers that had been ordered out of Manila the day before. They had left this morning and were en route to Indo-China and were now nearing Shinnan Gunto, or Dangerous Ground. It was decided that they should be recalled and hurled against the Mindoro beachhead. Since the moon phase the night of the 15th would be 0.5, it was judged that the attack had some chance of success.

These orders were sent to commander of Desdiv 43 Commander Kanma Ryokichi. He refused to consider them. His ships were too short of fuel, guns in need of service, and engines overworked and cranky. In truth, he judged his flotilla really too weak to contemplate such a thrust. Kanma continued on course for Indo-China, sending an explanatory apology for his failure to attempt the attack. Ironically, his ships lay over at Dangerous Ground, where they might well have made short work of crippled BERGALL if Hyde had followed his original orders to proceed there!

When Manila heard that Desdiv 43 would not be attempting its attack, there was a flurry of conferences. Field Marshall Terauchi, General Yamashita, and Admiral Mikawa and their staffs hastened to agree on some response. The Southern Army commander, aggressive as usual, wanted to launch a counterlanding. General Yamashita was opposed--it was bad enough that so much effort had been poured into Leyte; he wasn't about to subscribe to similar wasted effort for Mindoro. It was high time to prepare for the invasion of Luzon itself. The Army staff agreed with Yamashita that Luzon's defense was now priority, but they insisted that strong effort be made to at least forestall the use of airfields on Mindoro by the enemy. In addition, the Navy was eager to make some manner of offensive move using Shima's Second Striking Force. So a joint ad-hoc compromise operation was planned. A hybrid bombardment force would make a high-speed "penetration" on a hit-and-run raid to bombard the Mindoro beachhead while the Imperial Army parachuted a small infantry raid to hamper our airfield development.

One way or another, this was bound to involve the units of Shima's 5th Fleet, but in exactly what way remained to be fixed upon. But gathering these up immediately was impossible, for a considerable number of them were tied-down in the MYOKO affair. That activity had developed into a major rescue-at-sea and salvage effort, with a continuous stream of messages back and forth between Singapore, St.James, and Manila.

The morning of 17 December Shima’s Second Striking Force had hastily departed Camranh Bay after being discovered by an enemy bomber the previous day. At 1500 December 18th, Shima steamed into St.James, where NICHEI MARU had arrived earlier and was waiting to provision 2-YB. At the same moment, just to the south, the KASUMI and HATSUSHIMO were drawing up beside the wallowing MYOKO. They found the cruiser still on an even keel, and except for the mangled stern, rolling easily. She appeared in no danger of sinking. Captain Ishiwara blinkered that he was anxious for a tow attempt.

Scarcely had preparations begun when the Saigon airwaves crackled at 1530: Air-raid alert, for the whole St. James area. Dismayed, KASUMI and HATSUSHIMO moved off, as Ishiwara's tired crew manned the guns and anxiously peered at the skies. In St. James harbor, an equally frustrated Shima hastily gave orders to cast off, and Second Striking Force quickly put back to sea to avoid the anticipated raid. Two hours passed, and no attack developed. Saigon was passed by. At 1728 the alert was canceled as everyone breathed sighs of relief. Wasting no time, Shima promptly reversed course and put back into Saigon for his interrupted provisioning. KASUMI and HATSUSHIMO also returned quickly to the task at hand. It would be dark before long.

The KASUMI closed the leeward side of the MYOKO, passed a towline, and it was secured to the cruiser's anchor chains. Then, as HATSUSHIMO stood guard to seaward, the KASUMI moved slowly ahead. At 1733, strain was taken up, and MYOKO began to make headway. Speed was gradually built up, with course slowly shaped to the southwest for Singapore in the troughs of increasing swells.

As MYOKO's bow lifted and dipped between the swells the hawser of course drew taut, then slack, then taut again, putting a tremendous stress upon it. There was nothing KASUMI could do, for the cruiser was many times it's weight---it was hard enough to keep her on course and moving, let alone correct her yawing. At 0238, the inevitable happened. With a great crack and whipping, the tow line parted, snapping through the stormy skies to fall into the sea.

The MYOKO, rolling heavily, immediately fell off into the troughs of the mounting sea. At once, KASUMI put about to attempt the difficult task of restoring the tow in the darkness, while HATSUSHIMO scurried to keep an even sharper watch for sign of enemy submarines. If MYOKO was attacked now, she would be a sitting duck. The frustrated Imperial Navy officers might have been a little comforted if they had known just what bad days the 18-19 December were proving for the U.S. Navy as well. It was a real, and powerful, typhoon at sea. It caught and battered Admiral Halsey’s TF 38, damaging several carriers and actually sending three destroyers to the bottom.

The severe weather conditions now likewise forced outright abandoning of the towing attempt. The auxiliaries, two destroyers and the crippled cruiser now settled down to a nerve-wracking wait for improved seas. For four days they tossed and wallowed, unable to do anything but wait. At 1050 on 19 December they were joined by encouraging presence of of the HAGURO and CHIBURI. But even the HAGURO could not get a tow line secure in the wild seas. The wait continued, while news arrived of further disaster: the new carrier UNRYU had been torpedoed and sunk while en route to Manila. The forces available to oppose the Mindoro landing were being whittled away. Southwest Area Fleet could no longer tolerate further delay.

At noon 20 December the beleaguered squadron was in position 5-15'N, 104-45'E north of Malaya when orders came that KASUMI was to break off the rescue operation of MYOKO immediately and proceed as fast as possible to St. James to become the flagship of Admiral Kimura for a thrust against Mindoro. Southwest Area Fleet had at last finalized it's plans for a counter-attack against the Mindoro beachhead and Shima had received his final orders that same morning at 0819 with dispatch order 838 from VAdm Denkichi Okochi. An "Intrusion Force" under Radm Masanori Kimura – ComDesRon 2 – was to make a surface attack against Mindoro. Kimura wanted his old flagship back, having become quite attached to KASUMI since having to shift his flag from ABUKUMA to her during the battle of Surigao Strait. So at 1500, the KASUMI cast off her tow. She did not join Kimura until 22 December, further delaying the intended counterattack against Mindoro. (It did not take place until Christmas Eve).

Miles and miles away, that same morning saw one of the combatants complete its return home. The BERGALL made a triumphant entry to Exmouth Gulf at sunrise, and at 0745 tied up with ANGLER alongside an oil barge. She would not be staying long, just long enough to weld some plates on the torpedo load hatch. Then she would be underway again that afternoon for Freemantle. Her patrol had lasted 21 days, nine of which were spent north of the Malay barrier in enemy waters. The gallant BERGALL arrived at Freemantle at noon 23 December, just in time for Christmas.

Meanwhile, it remained to be seen what would happen to BERGALL’s victim. The KASUMI’s place was taken on 21 December by the CHIDORI, and major progress was made at 0900 23 December when the weather moderated enough for HAGURO herself to take MYOKO in tow. With the heavy cruiser’s powerful engines bent to the task, the ordeal was near its end. The remaining miles were crossed smoothly and at last, at 0238 on Christmas Day, the beleaguered cruiser safely moored at Seletar. She had been under tow seven days across submarine infested waters. It is one of the most tenacious, and least publicized salvage operations of the war.

It is an extraordinary story. Two warships – One American, one Japanese - had traded blows with one another, and each sent the other limping away. Both arrived home after an epic struggle by their crews fighting wind and wave. For Commander Hyde and the BERGALL’s bold crew, there came accolades in Australia and a glowing endorsement from the Squadron Commander J.F. Huffman:

"The Squadron Commander congratulates the Commanding Officer, officers and crew of the U.S.S. BERGALL, not only for the considerable damage inflicted on the enemy but on the magnificent achievement of bringing their damaged ship back. The decision to attempt this in view of expected enemy opposition reflects credit on an intrepid Commanding Officer and a Fighting Ship. All hands will bend every effort to get this stout-hearted crew back on the firing line as soon as possible."

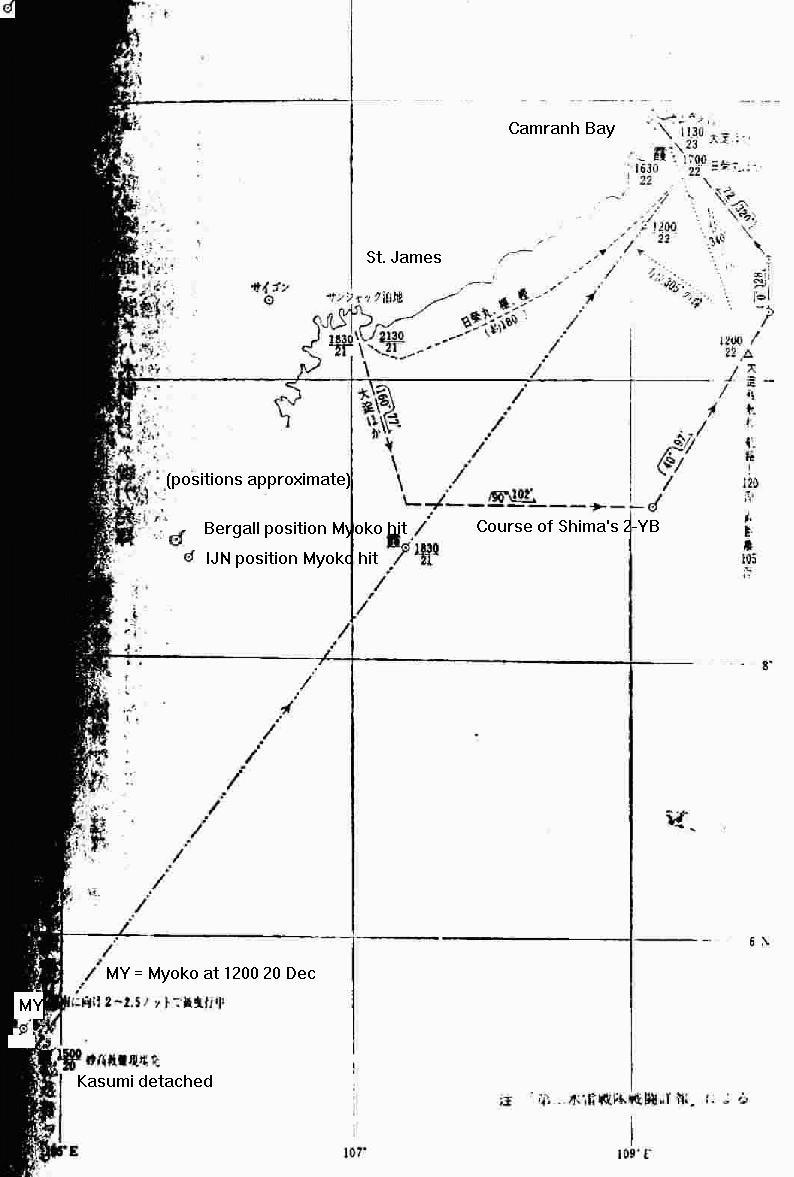

The USS BERGALL upon her triumphant return to Australia. The path of the USHIO's shell is clearly marked, having passed from port to starboard through the pressure hull.

For Captain Ishiwara and the crew of the MYOKO’s splendid achievement, and their rescuers, there were no commendations. The hard discipline of the Imperial Navy decreed that such courage and tenacity was to be expected, and could receive no official reward. And though plucky BERGALL soon went to sea again, unfortunately for Captain Ishiwara, his ship's injury proved beyond Singapore's ability to restore. The MYOKO's ruined aft section was cut off abaft No. 5 turret and the bulkhead there shored up to serve as the new fantail. In that state, without propellers and rudder, she was moored idle till the end of the war. BERGALL had essentially sunk her; but it seems safe to assume that getting home alive counted for something among MYOKO’s men.

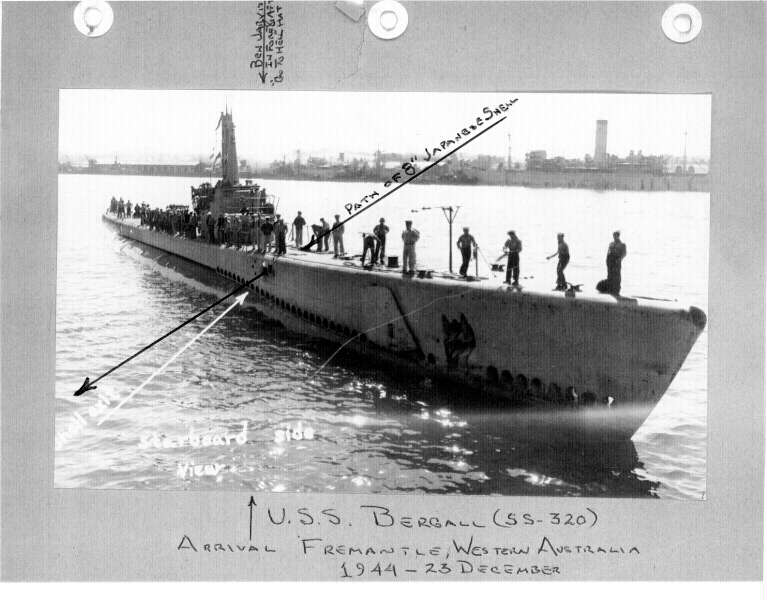

"Busted BERGALL's" victim: The heavy cruiser MYOKO lying wrecked at Singapore. This photograph shows her in Johore Strait, from the starboard quarter. This massive damage is not entirely the result of the torpedo hit, as what remained of the stern abaft turret No.5 was removed by repair men after her return. But by inflicting this damage, BERGALL effectively destroyed the cruiser; MYOKO never returned to action. (Author's collection)

Thus, though both combatants struggled and

staggered home, as Fortune decreed, only one returned to action.

As for the MYOKO, she languished post-war as a lodging ship at

Singapore until 2 July 1946.

On that date the ruined heavy

cruiser was taken out on a slow tow. Six days later, in the early

hours of 8 July, she was scuttled in the Straits of Malacca where

she remains – 150 meters deep - to this day.

Sources: USS BERGALL (SS 320), Report of Second

War Patrol

Signal log and Daily activity record, DesRon 2 War Diary,

December 1944

Signal log and monthly summary of action, 5th Fleet War Diary,

December 1944

Total Eclipse, Last Battles of the IJN, 1944-45 Unpublished

manuscript by Anthony Tully, 1996.

Silent Victory, The U.S. Submarine War against Japan , by

Clay Blair, Bantam Books, 1975, pp 596-597.

Japanese Cruisers of the Pacific War , by Eric Lacroix and

Linton Wells, USNI Press, 1997, pp 351-352

Crew members and correspondence from USS

BERGALL site