The crew of the new submarine carried out shakedown operations in the waters off New London and attack training at the torpedo range near Newport until 3 July. After returning to New London, the boat set sail for the Pacific on the 16th. Enroute to Panama, as remarked in Bergall’s war diary, the crew received “indoctrinational life guard duty training” near Puerto Rico when an Army training plane splashed about 1,000 yards away. The airplane crew “were unhurt and enjoyed the ride to Panama.” After transiting the Panama Canal on 24 July, the submarine departed Balboa on the 28th and arrived at Pearl Harbor on 13 August.

Bergall then engaged in two weeks of type training, firing nine torpedoes and taking part in one convoy exercise. She also entered dry dock to replace a squeaky load bearing strut before preparing for her first war patrol. Departing Pearl Harbor on 8 September, the submarine sailed to the Marianas, mooring alongside Holland (AS-3) in Tanapag Harbor at Saipan on the 19th. The next day, she headed west into the Philippine Sea.

On 22 September, Bergall’s bridge crew sighted another submarine, which dived shortly thereafter. After clearing the area, the American submarine radioed a contact report. While endeavoring to send a follow up message the next day, Bergall had to submerge quickly when a Japanese “Frances” twin-engined bomber came along and dropped a depth charge on her wake. As the submarine worked toward the assigned patrol station off French Indochina, four more Japanese planes harassed her progress, delaying the boat’s arrival off Cape Varella until the 29th.

After allowing five small ships pass by, Bergall battle surfaced on the 3 October in attempt to sink a 150-ton cargo ship with gunfire. She surfaced at long range, about 3,500 yards, and Bergall’s gunners opened fire with 40-millimeter and 5-inch guns. The Japanese cargo ship took at least one 5-inch hit and immediately turned for the beach. This attack was cut short, however, when a Mitsubishi F1M2 “Pete” observation floatplane flew into the area and forced Bergall to submerge.

For the next five days, she unsuccessfully patrolled the offshore shipping lanes before closing Phanrang Bay on the 8th. The next day, Bergall sighted a 700-ton cargo ship and fired three torpedoes, the first of which hit and completely demolished the target. A postwar records review, however, did not indicate any Japanese losses in that area, and Bergall did not receive credit for this sinking.

While operating close inshore on the morning of 13 October, Bergall sighted two cargo ships farther offshore--one estimated at about 2,000 tons and the other 1,000 tons--escorted by two small escorts. After maneuvering to seaward, the submarine fired four torpedoes at the larger target from about 2,000 yards. At that point, one of the escorts began to rapidly close Bergall. The submarine turned sharply, dived, and headed out to sea. The crew heard two loud explosions and breaking up noises, signifying the end of Shinshu Maru, a 4,182-ton cargo ship. Over the next five hours, Japanese forces tried to retaliate, dropping 30 depth charges and four aircraft bombs in an unsuccessful attempt to sink Bergall.

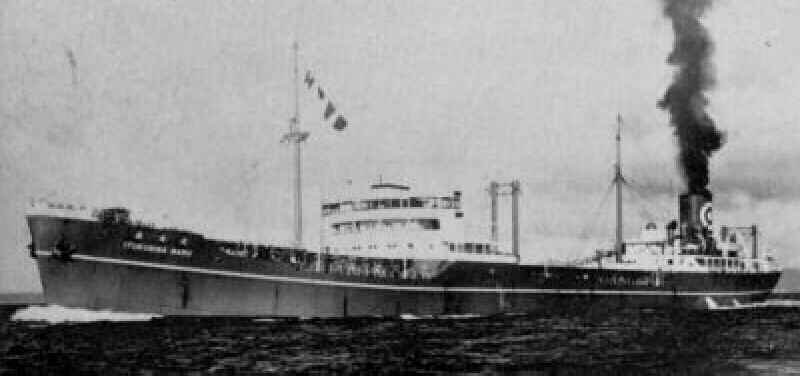

The submarine then moved farther south, cruising along a patrol line near Saigon until the 24th. She then received orders to patrol the Balabac Strait near Palawan. On 27 October, while conducting a night patrol on the surface, Bergall picked up four ships on her radar. She closed rapidly and, at a range of 3,500 yards, fired six torpedoes at a very large tanker. Shortly thereafter, multiple explosions accompanied by a large sheet of flame indicated four hits. The other cargo ship fled into shoal water, and the American submarine withdrew into Balabac Strait. Twenty-minutes later, the target pip disappeared from Bergall’s radar screen, marking the demise of Nippo Maru, a 10,528 ton tanker. It turns out that her sister ship in the convoy (The Itsukushima Maru) was of the same class and was also hit by a torpedo. She was found the next day, dead in the water and destroyed by Allied aircraft.

The next day, the submarine cruised south along the coast of Sarawak and passed through the Karimata Strait on 1 November. On the 2d, off the south coast of Borneo, she came across a small sailboat loaded with cargo. After the submarine stopped to investigate, the boat’s native crew leapt into the water on the opposite side of the sailboat. The Americans opened fire with 20-millimeter and 40-millimeter guns, destroying the boat “to protect our topside personnel from possible treachery.” The submarine then continued south, passed through the Lombok Strait and arrived in Freemantle on 8 November.

After a refit and drydocking in ARD-10, the submarine got underway for her second war patrol on 5 December. She passed through Lombok Strait late on the 8th and cleared Karimata Strait on 11 December. Two days later, while patrolling at night off the southern tip of French Indochina, Bergall’s lookouts sighted two Japanese warships moving away from her at 13 knots. The American submarine pursued on the surface and, after slowly gaining ground for three hours, managed to close the range to 3,300 yards. As noted in the war diary, owing to very shallow water, the submarine was forced to make “an attack on the surface like a PT boat.”

At 2037 on 13 December, Bergall fired six torpedoes at the larger target--now believed to be a heavy cruiser--and turned away. Three minutes later, a terrific explosion rocked the heavy cruiser Myoko, producing an immense sheet of flame which reached at least 750 feet in height. As the stricken warship’s companion--destroyer Ushio--had stopped to assist, the American submarine lurked nearby, planning to fire a salvo at her if given the opportunity. At 2100, however, as Bergall maneuvered closer, one of the Japanese warships fired two shells at the submarine. One landed in her wake close astern and the other--a dud round--pierced the forward loading hatch, tearing a large hole in her pressure hull as it exited the starboard side, just above the waterline. Evading two more salvoes, the American boat cleared the area with alacrity.

The wounded Japanese heavy cruiser Myoko, meanwhile, battled the damage caused by Bergall’s torpedoes. Her crew managed to extinguish persistent fires on the 15th and rig a tow line that same day. Over the next 10 days, she, and the eight other ships sent to help her, fought stormy weather in the South China Sea in a desperate attempt to reach port. On 25 December, despite severe storm damage which tore more of her damaged stern away, the heavy cruiser managed to limp into Singapore--denying the American submarine a complete kill.

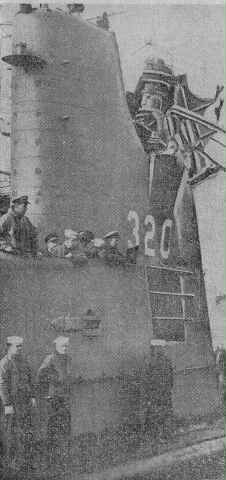

Bergall’s elated crew--believing they had sunk the heavy cruiser--spent the rest of the 13th extinguishing electrical fires, cleaning up the debris caused by the shell hit, and stuffing the ruined hatch with mattresses to keep out spray. Unable to dive the boat, the crew mounted all available guns and stood by to repel air attack the following morning. After reporting her predicament, the submarine received orders to rendezvous with Angler (SS-249), transfer the crew to that boat, and scuttle Bergall with torpedoes. After rendezvous with Angler on the 15th, Bergall’s commanding officer, Comdr. John Hyde, decided to “run the gauntlet” on the surface. Given the lack of enemy plane contacts, and fortuitous overcast weather, he gambled on continued good luck and set course for Australia. The two submarines traveled nearly 2,000 miles without incident, arriving at Exmouth Gulf safely on 20 December. Bergall received a Navy Unit Commendation for the night action of 13 December.

After the damage to Bergall’s pressure hull was repaired in early January 1945, the submarine’s crew conducted four days of training with new mark 27 acoustic homing torpedoes. Bergall got underway for her third war patrol on 19 January and commenced lifeguard duty off the Lombok Strait starting on the 26th.

At 0305 that evening, she picked up an approaching patrol boat on her radar and took up an attack position at a submerged depth of 200 feet. The submarine’s crew flooded a forward torpedo tube and, when sound bearings indicated the range had closed to 600 yards, fired one of their new torpedoes at the patrol boat. A few minutes later they heard one explosion and the target slowly disappeared from Bergall’s radar screen. At day break, the submarine came across wreckage and a drifting lifeboat. The crew picked up two prisoners and from them learned they had sunk a 174-ton coastal minesweeper.

The submarine continued lifeguard duty in Lombok Strait, dodging ship and aircraft contacts over the next several days. On 29 January, she fired another acoustic homing torpedo at a patrol boat, but this one missed. After several more days of fruitless patrolling, Bergall rendezvoused with Bluegill (SS-242) off Borneo, transferred the prisoners, and then continued west to the coast of French Indochina.

On 7 February, while submerged off Hannai Point, Bergall sighted two tankers guarded by four large escorts. Although the sea was smooth and glassy and the water shallow, the submarine closed to attack. At about 0936, she fired six torpedoes but did not see the results of the three hits heard minutes later because one of the nearby escorts spotted the torpedo wakes and closed Bergall’s location. The Japanese escorts started dropping depth charges almost immediately, with the seventh salvo coming very close. Bergall missed with the lone acoustic homing torpedo that she fired in self defense and was pinned down by repeated depth charge attacks for the next three hours. She scraped bottom several times, and her war diary suggested that the shallow water might actually have saved her--many of the Japanese depth charges did not explode, presumably because they hit bottom before reaching their set depth. Surfacing that evening, Bergall learned from nearby Flounder (SS-251) that the escorts had been driven off by a Consolidated PB4Y-1 “Liberator.” A postwar review of the records indicated that, while Bergall had only damaged a tanker, one of her shots had sunk the 800-ton Coastal Defense Frigate No. 53.

The submarine remained in her patrol area until 12 February, when she received orders to rendezvous with two other submarines to form a coordinated attack group. After rendezvous with Guitarro (SS-363) later that day, and Blower (SS-325) early on the 13th, the trio took up a patrol position off Cape Batagan, French Indochina. Despite numerous enemy plane contacts, which forced the American submarines to dive repeatedly, Bergall spotted a Japanese formation of two battleships, a cruiser, and three destroyers just after noon on the 13th. She closed to 4,800 yards and fired six torpedoes before diving to escape. Less than ten minutes later, the first of 15 Japanese depth charges dropped near her firing position. The boat shook violently but suffered only minor damage. While submerged, the crew heard three explosions, some a long way off--signs the other American submarines were in on the attack. Records reviewed after the war, however, indicated that the Japanese warships suffered no damage. The next day, Bergall proceeded to Subic Bay for a refit, arriving there on 17 February.

Following two weeks of repairs alongside tender Griffin (AS-13), the submarine put to sea for her fourth war patrol in early March. In company with Blueback and Blenny (SS-324), Bergall sailed to the coast of French Indochina and took up a lifeguard station off Cape Varella on the 7th. She stayed there, battling rough seas and dodging packs of fishing boats, until 15 March when she sailed north to rescue four American aviators spotted in a life raft. The enemy gave Bergall’s crew several bad starts during this time period, including one where Japanese escorts randomly dropped depth charges nearby and two others in which Japanese submarines fired torpedoes at her.

The American submarine sailed to a position off Java on 8 April, but more frequent Japanese air patrols forced Bergall to submerge almost every day. The submarine proceeded to Australia on the 14th, arriving at Freemantle on 17 April. Following a refit in drydock, which included cleaning the hull, fixing excessive rudder vibration, and installing a new surface search radar as well as one 40-millimeter and two 20-millimeter guns, the submarine conducted sound survey and training exercises until getting underway on her fifth war patrol on 12 May.

Bergall cleared Lombok Strait on the morning of the 18th and turned west, passing south of Kangean Island. At 0725, lookouts spotted a small coastal freighter creeping out of a nearby bay. Unwilling to waste a torpedo on such a puny target or to man the 5-inch gun for fear of air attack, the submarine closed rapidly on the surface and opened fire with both 40-millimeter guns. A dozen hits started a fire, and the freighter’s crew began abandoning ship. Just then, however, a Japanese plane approached; and Bergall submerged to avoid a counterattack. The damaged Japanese freighter escaped into Gedah Bay under this protective air cover.

Bergall sailed on through the Java Sea and took up a patrol position astride the Japanese convoy routes heading north out of Singapore. Joined there by Bullhead (SS-332), Hawkbill (SS-366), Kraken (SS-370), and Cobia (SS-245), she patrolled off the coast of French Indochina. The submarine also scouted the South China Sea during the Allied landings at Tarakan, Borneo. After a number of false contacts, Bergall finally spotted a small convoy in the early morning hours of 30 May. The crew manned guns and sank all targets: five barges and two tugs. As noted in the war patrol report, the “tugs tried to slip their tows and run for it but their speed of eight knots was sadly inadequate.”

Bergall then searched the Malay coast, spotting a four-ship convoy deep in the Gulf of Thailand on 12 June. Owing to the shallow water, the submarine sailed ahead to find a better attack position but was forced to submerge when a Japanese floatplane appeared overhead. Bergall surfaced that evening and headed north along the coast in search of the convoy. Just after midnight, near the Isthmus of Kra, a powerful explosion to port--probably either a magnetic influence or a remotely controlled mine--severely rocked the boat. The blast knocked out power to her motors, sheared numerous bolts in the machinery room, and jammed her rudder hard to port. A feared chlorine gas leak proved less worrisome, however, it “turned out to be a broken vinegar jug in galley which smelled strange to the lads when the ventilation system took it to the forward battery.”

Following temporary repairs, Bergall got under way, but the shock damage left her reduction gear noisy and full of asymetrical vibrations. Unable to attack successfully in this condition, she turned north for Subic Bay, arriving there on 17 June. Ordered home for more extensive repairs, the submarine sailed from the Philippines on the 20th, stopped at Pearl Harbor between 8 and 11 July, and passed through the Panama Canal on 27 July. She arrived at the Portsmouth (N.H.) Navy Yard on 4 August and it was there, during an extensive four-month overhaul, that the crew heard the news of the end of the war on 15 August.

Upon completion of these repairs, Bergall got underway back to the Pacific on 1 December. On the way, she conducted a series of post-overhaul training exercises before passing through the Panama Canal and reporting for duty with the Pacific Fleet on 18 December. Assigned to Submarine Squadron (SubRon) 1, Bergall spent the next year--aside from one cruise to Guam and back--operating locally in Hawaiian waters. In November 1946, she received another overhaul, which included the installation of a new surface search radar.

In light of the growing tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union, emphasized by President Truman’s 12 March 1947 message to Congress articulating American willingness to provide military aid to countries threatened by communism, the Navy began planning for a possible confrontation with the Soviet Union. One of the training measures devised to give submarine crews experience in case of such a conflict was the “simulated war patrol,” a mission upon which Bergall embarked in April 1947.

Underway from Pearl Harbor on the 1st, Bergall sailed north for a patrol in the Bering Sea. She ran into snow squalls on 8 April before arriving at Adak two days later. After a brief stop at Attu on 14 April, Bergall practiced maneuvers in the Bering Sea in late April. She conducted target practice against the ice pack on the 20th and carried out a reconnaissance exercise near the Pribilof Islands on the 23d. The submarine sailed to Dutch Harbor on the 25th, then moved on to Kodiak, arriving there on the 28th. She then took part in antisubmarine (ASW) training with land-based Patrol Squadron (VP) 10 in early May before turning south to arrive in Seattle on the 14th.

There, Bergall conducted several reserve training dives, a few more ASW exercises with aircraft--this time with planes from the naval air station at Whidbey Island--and opened ship for visitors while in Lake Washington on 23 May. Following another reserve training cruise on the 31st, the submarine returned to Pearl Harbor, mooring there on 8 June.

Later that summer, Bergall put to sea in company with Brill (SS-330) and Bugara (SS-331) for a coordinated attack exercise against Iowa (BB-61) in the Hawaiian Islands. Taking up a position in the Alenuihaha Channel, the submarines attempted to intercept the battleship as she made a high-speed run between Maui and Hawaii. Although the battleship enjoyed land-based air cover, and made several radical course changes in an attempt to throw off her pursuers, the submarines still achieved four “successful” attacks against the battleship, including one by Bergall from a range of only 950 yards.

Bergall remained in Hawaiian waters, save for a single voyage to San Diego for the Navy Day celebrations that November, until 14 May 1948. On that day, she sailed to San Francisco where she entered the Mare Island Naval Shipyard on 7 June for a four-month overhaul. The boat received new batteries, a new sonar suite, and a motor overhaul before leaving California on 21 October and arriving back in Pearl Harbor on the 29th. In preparation for experiments to be conducted during her second simulated war patrol, Bergall’s crew took on board two scientists from Columbia University and installed gravity-measuring equipment inside the submarine.

Underway from Pearl Harbor on 3 December, Bergall slowly sailed southwest, diving at 50-mile intervals to take underwater gravity measurements. She crossed the equator on the 9th near the Gilbert Islands and moored at Brisbane, Australia, on 20 December. A week later, she headed north toward Guam and, after taking more measurements every 50 miles, the submarine arrived in Apra harbor on 7 January 1949. After disembarking the scientists and unloading their equipment, Bergall commenced two weeks of shore bombardment and ASW exercises, including a mission against Astoria (CL-90), James E. Kyes (DD-787), and Shelton (DD-790), in and around the Mariana Islands.

Departing for Japan on 20 January, the submarine conducted more ASW exercises out of Sasebo and in the waters off Okinawa. She also provided target services to 7th Fleet land-based patrol aircraft. During these exercise, Bergall discovered that, at least during calm weather, patrol planes could drop sono-buoys near her and vector in supporting destroyers who successfully “pinned down” the submarine. In rougher weather, swirling water smothered the passive sono-buoys with white noise and the submarine always escaped. Bergall departed Okinawa on 15 February; and, after a brief refueling stop at Midway, she returned to Pearl Harbor on the 28th. The submarine then conducted local operations in Hawaiian waters for the remainder of the year.

On 6 June 1950, Bergall got underway from Pearl Harbor for the east coast. The Korea conflict started on the 25th and the Bergall was expected to arrive on the 29th. When she arrived 2 days early there was confusion and thoughts that the canal may be under attack until the boat could clear her presence with the port authority. She passed through the Panama Canal on 1 July, and arrived at New London on the 11. There, she was assigned to the Operational Development Force (OpDevFor) and soon began doctrinal and experimental exercises with Atlantic Fleet forces. In addition to local exercises, the submarine also conducted several training cruises up and down the east coast. In September 1950, she visited Bridgeport, Conn., and Brooklyn, N. Y.; and, on 6 June 1951, the submarine embarked on a training cruise to the West Indies. Bergall visited Cuba--stopping at Guantanamo Bay and Havana--and Port-au-Prince, Haiti, before returning to New London on 10 July.

A month later, the submarine loaded 42 mark 10 drill mines and, on 15 August, conducted a submerged minelaying exercise in Block Island Sound. Bergall then remained in New London until 8 November, when she proceeded to the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard to commence a fleet snorkel conversion. There, between 9 November and 9 April 1952, shipyard workers installed a new streamlined sail and the air intake and exhaust tubes of the snorkel system--allowing the submarine to operate her diesel engines while submerged at periscope depth.

Over the next two years, Bergall operated locally out of New London and conducted two training cruises to the West Indies, where she visited the Bahamas, Cuba, and Key West. She also held three more minelaying exercises in Rhode Island Sound, demonstrating the advantages of a snorkel-equipped submarine for this type of operation. In addition, the submarine participated in ASW training with friendly destroyers and aircraft. During one such exercise, in the evening of 31 October 1954, Norris (DE-859) accidentally ran over the submarine during a simulated attack. The collision smashed in Bergall’s sail, crushing her radar mast, snorkel head, and tearing out wiring and piping. As her pressure hull was unharmed, the submarine proceeded to the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard for repairs.

After this work was completed, Bergall resumed her familiar routine of development exercises out of New London on 16 December. These included a training cruise to Puerto Rico and Jamaica in January 1955, another minelaying exercise off Block Island in March, and tests with the Underwater Sound Lab at Bermuda in June. Later that summer, the submarine began preparations for an overseas deployment with the 6th Fleet in the Mediterranean. From 2 May to 4 June 1955 she escorted replacements for the 6th Fleet to Gibraltar, then returned to antisubmarine evaluation and training in the western Atlantic and Caribbean, broken by a three-week patrol in the North Atlantic during the November 1956 Suez crisis.

Underway from New London on 9 November, the submarine crossed the Atlantic and arrived at Lisbon, Portugal, on 20 November. After a short visit, she passed the Strait of Gibraltar sailed to Nice, France, arriving there on the 26th. Over the next six weeks, in between various ASW exercises with units of the 6th Fleet, Bergall visited ports in Italy and Spain and familiarized herself with the waters of the western Mediterranean. The submarine returned to New London on 28 January 1956.

In addition to her usual routine out of New London, Bergall provided target services for the Sound School at Port Everglades, Fla., in May; visited Halifax, Nova Scotia in June; and conducted more development exercises at Bermuda in August. Finally, on 21 October, the submarine reported to the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard for an overhaul. While there, shipyard workers installed new sonar and related equipment.

Underway for her shakedown cruise on 7 June 1957, Bergall sailed south to Fort Lauderdale, Fla., for two weeks of local operations and target services before returning to New London. In early July, she turned south again, this time providing services to the Underwater Sound Lab at Bermuda. After returning to New London on 22 July, the submarine’s crew carried out routine maintenance and other preparations for the boat’s second cruise to the Mediterranean.

Departing New London on 31 August, Bergall headed northeast across the Atlantic, arriving in Rothesay, Scotland, on 13 September. Ten days later, the submarine turned south and, after a brief refueling stop at Portland, England, passed through the Strait of Gibraltar on 7 October. Bergall spent the next seven weeks in the Mediterranean, conducting operations with units of the 6th Fleet at sea called "Operation Strikeback" and visiting Piraeus and Patras in Greece; Valleta, Malta; and stopping at Catania and Naples in Italy. She turned for home on 23 November, arriving in New London on 7 December.